This article explores the effects on staff of major workplace change from a psychosocial perspective. It draws on current research and established models to promote understanding and recognition of the inevitable fallout from imposed changes to established work procedures.

The elephant in the workroom

That change is a stressor has been asserted for many centuries:

Nothing that is familiar appears unaccountable or difficult to comprehend. But no sooner do we reason, meditate, and reflect on new things, a thousand scruples spring up in our minds. Prejudices and errors of sense do from all parts discover themselves to our view; and, endeavouring to correct these by reason, we are insensibly drawn into uncouth paradoxes, difficulties, and inconsistencies, which multiply and grow upon us as we advance in speculation, till at length, having wandered through many intricate mazes, we find ourselves just where we were, or, which is worse, sit down in a forlorn scepticism.1.

Despite this knowledge we are compelled to re-enact the ancient drama: defensiveness, avoidance, intrigue, conspiracy, hurt, anger, attack, despondency, and gossip are palpable and self-reinforcing during workplace disruptions.

The high road of self-protection

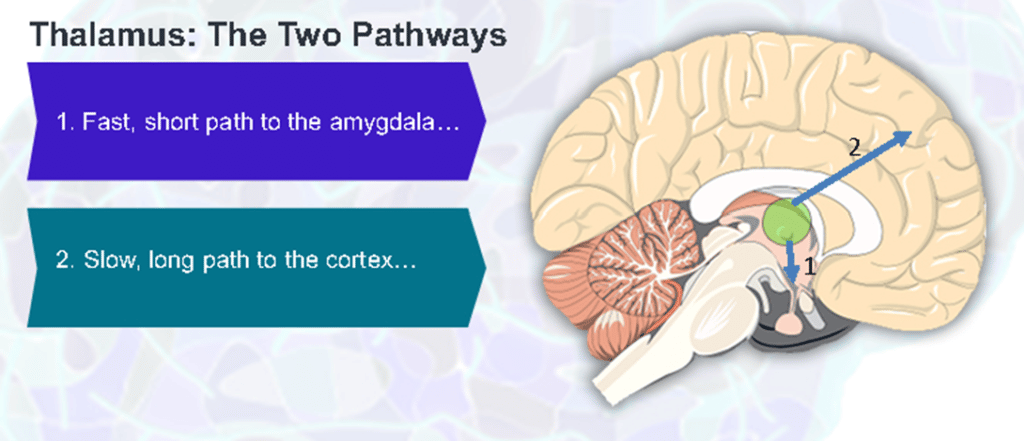

The structure of our triune (brainstem, limbic, cortical) brains has evolved with safety as an over-riding imperative. It has been a relatively recent discovery that not all the neurons in our brains are the same (more about this further down). Neurons in 1 above are FASTER and the distance covered SHORTER than in 2. Thus, information from our environment (sensation) dispatched from the thalamus reaches the amygdala (the ‘smoke detector’: fear/threat detection, stress response initiation) BEFORE the pre-frontal cortex (‘executive control’: comprehension, reasoning, impulse control). Sometimes it is better to act before we think.

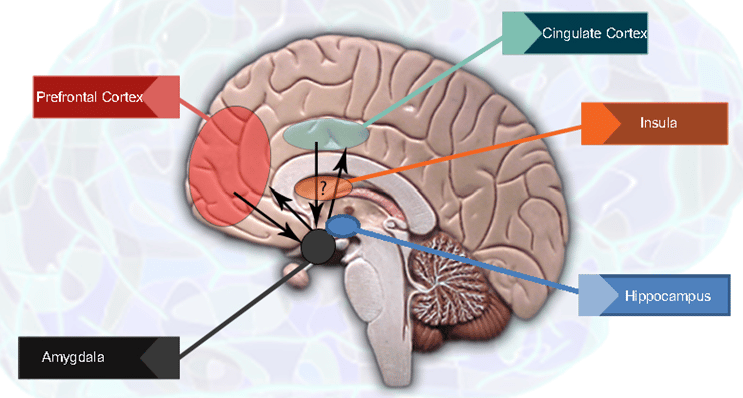

Additionally, amygdaloid hyperarousal impairs ‘healthy’ brain functions including reasoning, memory consolidation (Hippocampus), internal awareness (Insula), and emotional regulation (Cingulate Cortex).

Herein prolonged workplace change stress intersects the negative health and wellbeing impacts of the genesis and exacerbation of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Interpersonal Neurobiology

1. The Survival Edge

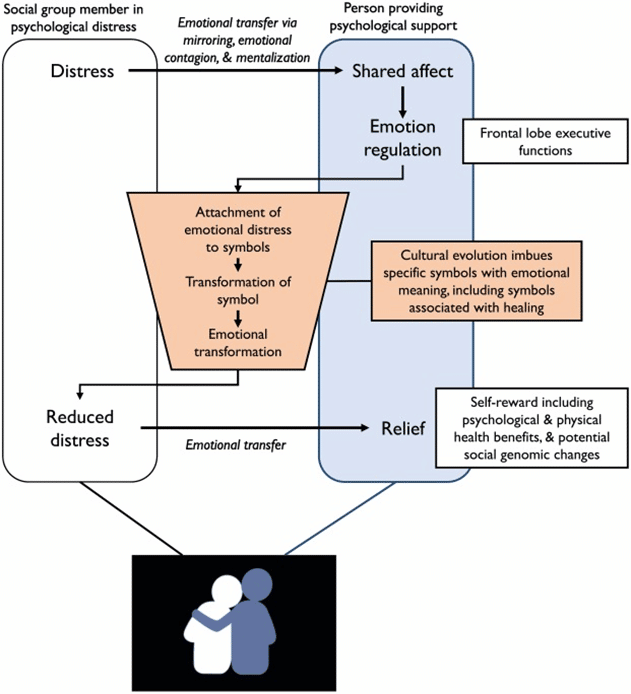

…mirror neurons explain(ed) many previously unexplainable aspects of the mind, such as empathy, imitation, synchrony, and even the development of language. One writer compared mirror neurons to ‘neural WiFi’- we pick up not only another person’s movement but her emotional state and intentions as well.2.

Researchers postulate that spindle neurons (names include Mirror and Von Economo)- bigger and faster than other neurons- evolved to accommodate increased brain size in animals such as primates, whales, and elephants. Further, they appear to have been co-opted by brain centres crucial for social behaviour- particularly the insula (see above)- which has specific roles in both enteroception (awareness of self) and the generation of social emotions such as empathy, trust, guilt, embarrassment, love, and, even a sense of humour.3. Indeed, there is a growing notion that self-awareness and social awareness are part of the same functional brain system.

Thus, spindle neurons afford us a rapid read on emotionally charged, volatile situations, enabling us to quickly adjust to changing social contexts by making accurate, split-second judgments- especially about who we can trust and who is likely to provide reciprocal protection.

2. Emotional Contagion

..But our mirror neurons also make us vulnerable to others’ negativity, so that we respond to their anger with fury or are dragged down by their depression.2.

Emotional contagion is often a focus term in coping with workplace stressors. In a complex multi-layered dance of culture, memory and experience: subconscious mirroring or mimicry of smiles, frowns, or other emotional expressions greatly affects our behavioural predisposition.

Importantly, the effects of emotional contagion correlate with valence7.: positive emotional contagion leads to fewer cognitive errors and workplace accidents whilst the reverse is observed for negative emotional contagion.

So, you think you know what’s going on?

Confounded by yet another adaptive feature of the brain (its ability to confabulate, that is, to create an alternative version of reality when sensory input is so disconsonant with a person’s sense of self that it is deemed a threat to survival), not only can we never fully know the state of our co-workers’ minds, but what we think we know may well be wrong.

Some of the puzzle pieces

1. Work-self identity

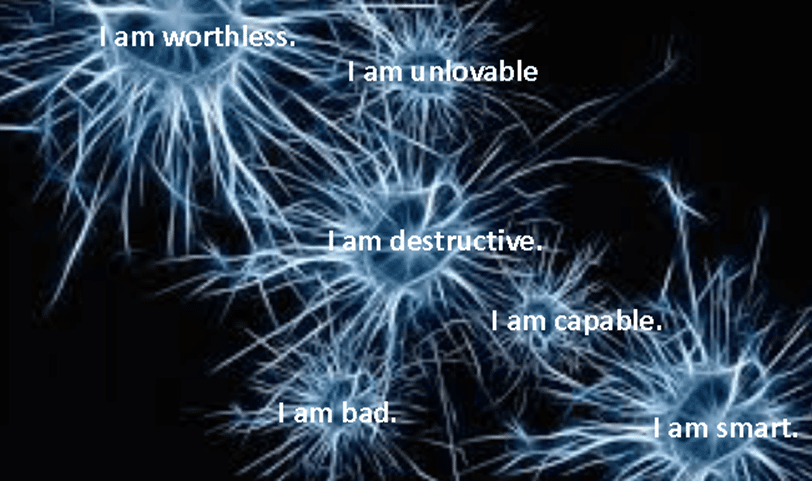

Work inevitably and differently informs each worker’s self-concept as workplace sensory experiences are consolidated as memories in the neuroplastic networks of an individual’s Hippocampus. To protect and promote their work-self identity, individuals may resist a new logic that threatens this identity.

2. Organisational culture

Organisational researchers have examined defence tactics to understand problematic organisational cultures that appear unable to respond to change. Learning in organisations is inhibited by defensive routines, for example, procrastinating, crowding out disruptive topics, asking pointless questions, creating barriers to change, not passing on new procedures, maintaining taboo topics, engaging in strategic ineffectiveness, and sending mixed messages.

3. Predisposition

The psychological state of the individual can affect the processing of emotional information; for example, people with depression fail to differentiate between positive and non-emotional content.

PTSD and chronic stress can result in amygdaloid changes creating states of dysregulated physiological arousal. Affected individuals display more emotional lability: they are more likely to ’fly off the handle’ when confronted with change.

Attachment insecurity is also a fundamental determinant of inter-personal behaviour 5..

Genetic factors contribute to change stress response. Besides affecting the development of various brain structures and circuitry, the production and regulation of neurotransmitters and associated enzymes is determined by an individual’s genome.

Epigenetic changes similarly influence an individual’s ability to cope with change; in particular childhood adversity and abuse survivors are prone to poor emotion and impulse regulation.

Personality traits including intro/extroversion, behavioural inhibition, harm aversion, neuroticism and other tendencies have been cited as co-factors in change response.

Coping tips- the collective wisdom

- Try to remember that work change stress is not permanent and bad feelings will dissipate over time as you adjust to new routines.

- Take regular breaks to help calm yourself down- even a short walk can help.

- Remember to breathe. Research reveals that 80% of office workers report noticing that they stop breathing many times a day. Diaphragmatic breathing plays a central role in regulating autonomic arousal.

- Acknowledge your perfectionism: you may find that you can improve your work considerably by lowering your standards slightly during times of change.

- Practice mindfulness: active regular observation of your in-the-moment body sensations, thoughts, and feelings can stabilise dysregulated arousal and promote higher level learning from stressful experiences.

- Try not to take things personally: we are all prone to misinterpret others’ behaviour as attack.

- Look at the big picture: widening your perspective to include the entirety of your life can arrest the downward spiral of catastrophisation.

- Be vulnerable: don’t be afraid to admit your challenges and fears and remember that others are going through the same thing as you.

- Spread words of appreciation: offer at least three positives (in the form of smiles, positive feedback, congratulations, etc.) for every one negative you put out, whether it be criticism, a frown, etc.

- Try to recognise and change rigid thinking: established patterns of judging bind us to the past.

- Ask for help if you need it: consider that the healthiest amongst us know when to seek professional guidance and support.

- Consider stress management self-help strategies including yoga, qigong, progressive muscle relaxation, autogenic training, and exercise programs.

How a psychologist can help

Disruptive experiences are opportunities for learning, yet, people often resist them. This tendency is evident in individual experience and organisational behaviour 6..

Individual counselling should be considered if work stress is impacting your personal life: signs and symptoms may include intrusive thoughts and/or memories, avoidance of people or conversations related to work, changes in general mood, interests and motivation, and recurring nightmares or difficulties sleeping or concentrating.

Psychologists may utilise or adapt evidence-based approaches including cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), and emotion-focused therapy (EFT).

Employee assistance programs are useful for organisations preparing for change as they enable professional support to be accessed freely by workers.

If you or your organisation could benefit from engaging the services of a psychologist, please feel free to contact us for more information.

References

1. Berkeley, G. (1710). Treatise concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge. Dublin: Aaron Rhames & Jeremy Pepyat, Skinner Row.

2. Van Der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score, pp. 59-60. United Kingdom: Penguin Random House.

3. Chen, I. (2009) Brain Cells for Socializing. Smithsonian magazine. Washington: Smithsonian institute.

4. Cauda, F. et al. (2014). Evolutionary appearance of von Economo’s neurons in the mammalian cerebral cortex. Front. Hum. Neurosci.

5. Brown, D.P., Elliott, D.S. (2016). Attachment Disturbances in Adults, pp. 288-292. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc.

6. Gillespie, A. (2020). Disruption, Self-Presentation, and Defensive Tactics at the Threshold of Learning. Research Article https://doi.org/10.1177/1089268020914258

7. Goddard, A.W. (2017). The Neurobiology of Panic: A Chronic Stress Disorder. https://doi.org/10.1177/2470547017736038